Basic HTML Version

8

TUALATIN CENTENNIAL

January 3, 2013

into Portland.

1858

—The “Hoosier,” a

small steamboat. plied the

Tualatin River for a short

time.

1860

—Many settlers

went to the Idaho mines.

1865

—The Little Red

Schoolhouse was built on

the corner of Avery and

Boones Ferry Road.

1865

—The steamboat

“Yamhill” plied the river de-

livering farmers goods to

market.

1867

—Washington Coun-

ty erected a toll bridge to re-

place the old free bridge at

Bridgeport.

1868

—The steamwheeler

“Onward” navigated the riv-

er.

1880

—A fierce storm

raged through the Valley,

toppling trees like tooth-

picks.

1880

— Farmers began

draining the swamps and

groving products, especially

onions, on the rich beaver-

dam soil, and found some

huge bones, thought to be

from a prehistoric animal.

1887

—Chinese laborers

laid a narrow gauge railroad

through the area. John

Sweek platted out a new

town site around the new

train station, naming it “Tu-

alatin.”

1889

—The first east-west

railroad train came through,

and a store and hotel were

built close by.

1892

— John L. Smith

brought his extended family

TUALATIN

TIMELINE

Continued from page 6

Continued on page 12

By SAUNDRA SORENSON

Pamplin Media Group

W

hen Tualatin High School cel-

ebrated its 20-year anniversa-

ry at the start of the school

year, the Timberwolves had a

lot to be proud of: a record of extensive

community service, 16 state championships

in athletics, a drama and a music depart-

ment that could boast several tours nation-

ally and internationally. Facilities also

looked as fresh as they did in 1992.

But it was hardly the first Tualatin High

School.

The original Tualatin High School was

established during a boom time in the city’s

development. Historically, a rising demand

for educational facilities is a great economic

indicator, and this was especially true in

Tualatin, where John L. Smith’s 1890 arrival

in town further propelled Tualatin’s status

as a financially viable place to live and

work. His Tualatin Mill Company venture

combined the town’s relocated sawmill

with logging and lumber businesses, pro-

viding steady salaried work for an increas-

ing population.

Farming families and the families of

skilled laborers had produced a school-

aged population which, according to school

records of the time, was then at around 90.

This was not an exponential increase

from 30 years before, whenWashington

County School District 25’s sole one-room

schoolhouse was overflowing with 38 chil-

dren. A new, larger red frame school was

built around 1863 on Boones Ferry Road,

forming districts 25 and 26 — until a fire

claimed the older log cabin school in 1866.

The newer structure that remained

standing was put up on jacks more than 30

years later in order to add a new first floor

— and a complete four-year high school

program. In 1911, the building was once

again raised to meet the changing needs of

the student body, and toilets and a central

heating systemwere added.

Incoming Tualatin Heritage Center presi-

dent Art Sasaki identifies his father, also

Art, as one of eight members of the Tuala-

tin High School graduating class of 1927.

Until Tualatin High School reopened as

we now know it in the early 1990s, 1936 was

its final graduating class.

From that point on, teenage Tualatin stu-

dents were given the choice to attend one of

the far more spacious nearby campuses: ei-

ther Sherwood or Tigard high schools. (By

the time the younger Art Sasaki was in

school, the split happened as early as sixth

grade. He opted to attend Sherwood, he said.)

This opened up the top two levels of the

Tualatin schoolhouse. Even so, primary

school grade classes had to be held at City

Hall.

By the time the younger Art Sasaki was

in school, he said the split happened as ear-

ly as sixth grade. He opted to attend Sher-

wood schools.

With Tualatin’s remaining students still

scattered round town, the school board de-

cided to modernize with a building large

enough to give each grade its own room—

and to invite students from the much small-

er nearby Tonquin and Malloy districts to

attend. The project used premade plans

from another school and was funded in part

by the Public Works Program, in part

through land sales.

The old three-story schoolhouse then be-

came an apartment building before being

demolished some years later.

Although the city’s sons and daughters

completed their education in surrounding

towns, they held fast to their Tualatin roots.

Farmer’s daughter Nellie Wesch worked

tirelessly as a caddie at the Tualatin Coun-

try Club and ended up financing her way

through college not through her earnings

on the green, but through a collection put

together by regular golfers such as Julius

Meier. Wesch Returned fromwhat was

then Oregon Agricultural College and be-

came a popular teacher at Tigard High

School.

“She taught business education, typing,

accounting, book-keeping. In fact, several of

our members here had her as a teacher.

They attribute their success in their ca-

reers to her,” said Larry McClure of the Tu-

alatin Heritage Center.

The Tualatin side of the school district

grew to include three elementary schools,

Tualatin, Byrom and Bridgeport. It wasn’t

The history of Tualatin

schools show countywide

collaboration

An educational Odyssey

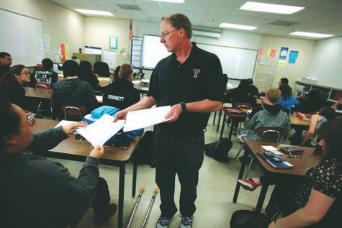

TIMES FILE PHOTO: JONATHAN HOUSE

Tualatin High School math teacher Mark

Dolbeer grabs homework assignments

from his students. He retired last spring

after 29 years of teaching. At left,

Tualatin Grade and High School was built

in 1900 and closed down in the 1930s